Non-Turing-Computation

Whats 19*91 ? Anyone who knows a bit about multiplication can tell that its 1729 (this also happens to be the Hardy-Ramanujan number). We humans do a lot of such computations every day.

50% discount on rides above 300 on Uber.

Our brain is wired to compute the price of an item listed with the given constraint and find out the best choice.

Let's try to answer a more difficult question. Is the below number prime ?

759301153995587786295940234337835566939818242933338764992626636151840060018287495175071640381085598621485324153512723306029347944398765220195985610285655148360429689570446991855700752025872155835192912833873171105200576475258000980674946417119578990569901912595362864383826160631207564428245219788870979717427639960592692739718067446610883944074742923064162539957869762709941009094660335117010525554194337335483429829570293294530317689382387199365645018871418582530303530942736407739032184541272768141863716754690767416741919411494261600447044209989519846225463497405337399025250428219525640436125838929594312133227We quickly realize that the problem has escalated in complexity and we need more powerful methods than our handy mobile app calculator to tell the answer. Although there are some fancy algorithms to test the primality of a number, but most of them require some amount of non-trivial computing.

Humans soon found the need for inventing devices to help with such hard arithmetic operations and hence came to be the calculator.

The first Calculator

A modern iPhone calc app

The earliest of these devices were just able to multiply and add numbers. Clearly we have come a long way. It's interesting to look at how computers add numbers today. This is the circuit for adding two bits :

Here S is the sum and C is the carry bit. Remember that the only numbers you can add in this are 0 and 1 and therefore can add upto only 4 combinations :

Inputs

Outputs

A

B

Carry

Sum

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

1

0

1

1

1

1

0

Our computers have so many of such circuits to add bits very very very fast which enables us to a wide range of tasks from watching movies, playing CS:GO or training neural-networks.

So what all things do we need apart from an adder or a mathematical calculator to do these complex tasks. Clearly adding, multiplying and dividing numbers won't be able to scan your finger print and let you access your computer. Let's try to answer this question of completeness and find the set of tools required to do all computation required by us.

Finite State Automata

We humans do very complex string matching which enables us to do a variety of interesting tasks, one of which is reading this very blog. It's interesting that our brain not only does text-matching in trivial ways, but also in some non-trivial and non-intuitive ways. Let's try to read this piece of text.

Aoccdrnig to a study at an Elingsh uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.

There are varied application of text-matching ranging from DNA Profiling, Google Search which powers the web and Parsers which lets us write and compile/interpret these wonderful pieces of code that we execute.

Regex matching has become the bread and butter of computer science. Let's try to get an insight on how computers do it.

The origins of regex matching takes us to Finite State Automata.

Definitions first :

A finite-state machine (FSM) or finite-state automaton (FSA, plural: automata), finite automaton, or simply a state machine, is a mathematical model of computation. It is an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The FSM can change from one state to another in response to some external inputs; the change from one state to another is called a transition. An FSM is defined by a list of its states, its initial state, and the conditions for each transition

Let's look at an example to understand this :

This machine can be on one of two states Locked and Unlocked. The initial state is Locked. When we push the locked state, nothing happens, which is represented by a self-loop arrow from Locked state to itself. Whereas when we insert the coin, we move to the Unlocked state and stay there as long we insert more coins we can stay there. When we push, we go back to the Locked state.

Simple enough right ? But what does this have to do with Regular Expressions ?

Let's look at a simple regular expression. p+qr+. This accepts strings starting with any number of p's ending with any number of r's and has exactly one q in between.

Example of accepted strings are :

pqr

ppqr

pqrrrrr

Unaccepted strings are :

qr

pqqr

pq

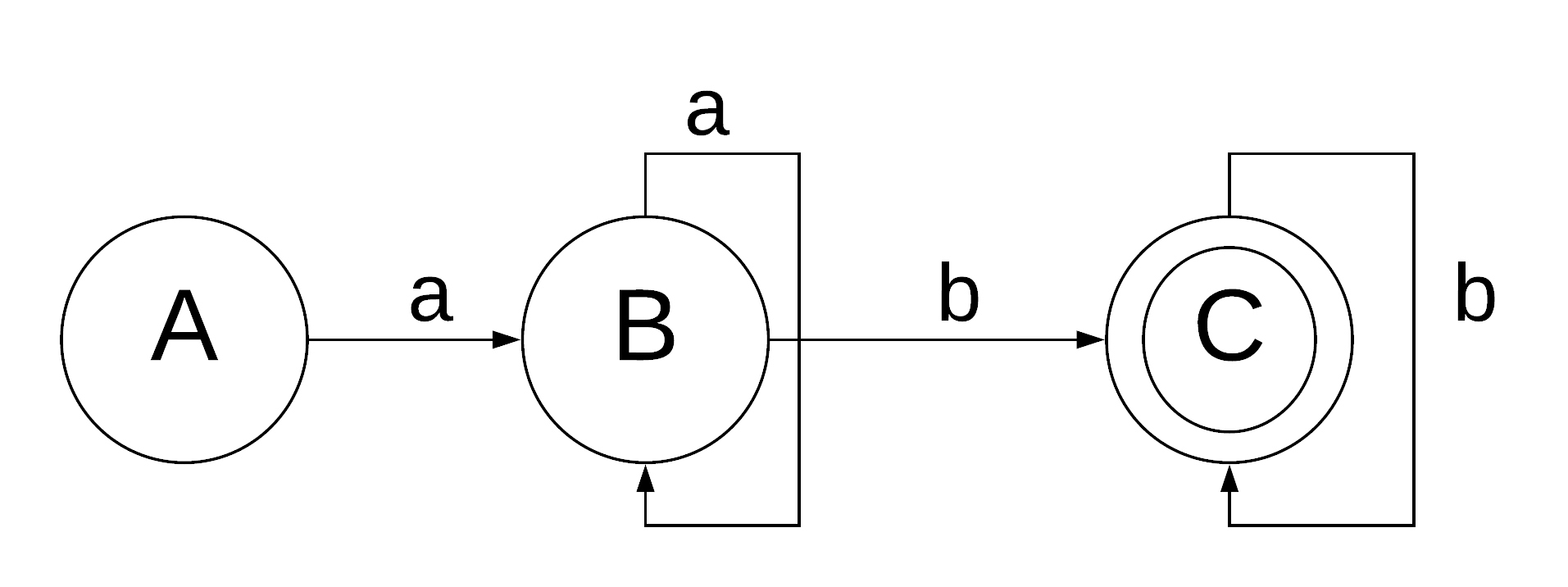

Let's try to build a state-machine for this.

Inititally we are in state A. When we find a p we move to state B and stay there as long we get p and then we move to state C when we get an Q and finally to state D when we get R.

The state machine goes to the accepted state D when it finds a string which matches the regex.

It can be mathematically proven that all regular expressions can be converted to a finite state-automata and there are many libraries that do these very well like the one discussed in Regex to automata.

So, is finite state machine the end of the world ?

Clearly not! If these finite state machines could solve all our needs then why haven't we still colonized Mars ?

Let's try to build a regular expression for accepting strings like aabb, aaabbb, aaaabbbb etc. More specifically of the form aⁿ bⁿ.

Is the above FSM a correct representation of the machine that accepts aⁿ bⁿ. Nope! It accepts strings of the form a+b+.

We want the number of a's to equal number of b's. But how do we count using an FSM ? Are we not smart enough to build one yet or there is an inherent limitation in Finite State Automata that it cannot do these kinds of computations.

Using the Pumping Lemma and after hours of disappointment we can prove that this is indeed beyond the reach of FSM's.

Intuition says that we are not able to keep track of the count and we need some way to do that. We need something like a variable(s) to store information. This brings us to our next model of computing : Push Down Automata.

Push Down Automata

The return of definitions :

A finite state machine just looks at the input signal and the current state: it has no stack to work with. It chooses a new state, the result of following the transition. A pushdown automaton (PDA) differs from a finite state machine in two ways:

It can use the top of the stack to decide which transition to take.

It can manipulate the stack as part of performing a transition.

A pushdown automaton reads a given input string from left to right. In each step, it chooses a transition by indexing a table by input symbol, current state, and the symbol at the top of the stack. A pushdown automaton can also manipulate the stack, as part of performing a transition. The manipulation can be to push a particular symbol to the top of the stack, or to pop off the top of the stack. The automaton can alternatively ignore the stack, and leave it as it is.

Put together: Given an input symbol, current state, and stack symbol, the automaton can follow a transition to another state, and optionally manipulate (push or pop) the stack.

So what do we do with this stack ? We do not yet realize the power that we have got. First things first, we try to solve the problem that Finite State Automata could not.

Let's try to get our automata to accept aⁿ bⁿ.

An greedy way to solve this is to keep adding all the a's to the stack and pop one a for each b that we encounter. At the end of the process if the stack is empty we have a correct string. Hmmn, looks correct doesn't it ?

Will it accept aabb. Yes. Will it also accept abab or abba. Ohh, now we realize that even a small mistake in specification our how our PDA works can lead to incorrect results. We have in a way introduced a bug in our program and we have not even started writing code.

So to fix this bug, we add a condition that we don't push a's to the stack after we encounter a b.

It is interesting to see what all can be done using Push Down Automata's. For us to get a sense on how powerful PDA's are we have to delve into the world of regular, context-sensitive and context-free grammar's.

Language consists of a set of strings which are considered "accepted". A grammar is a set of rules for producing all such strings in the language. NOTE: Till now we were just concerned about accepting strings. Now we are getting into the business of generating strings (possibly all) in a particular language defined by a particular grammar.

Regular Languages

Let's formally define a regular language.

The collection of regular languages over an alphabet Σ is defined recursively as follows : The empty language Ø, and the empty string language {ε} are regular languages. For each a ∈ Σ (a belongs to Σ), the singleton language {a} is a regular language. If A and B are regular languages, then A ∪ B (union), A • B (concatenation), and A* (Kleene star) are regular languages. No other languages over Σ are regular.

We have already been using this definition of a regular for writing regular expressions. (a*b*)∪(c*d*) is a regular expression which uses the operators that we just defined above. We also know the limitations of this language in the sense that it cannot produce strings of this format aⁿ bⁿ.

Context Free Languages

Now let's look at context-free languages. These are closely related to Push Down Automata's since for each context free grammar, there will exist a PDA which can accept all strings generated by this grammar.

Going back to our previous problem of generating aⁿ bⁿ. Let's try to define a grammar for this.

S --> aSb | ab | ε

This means that we can relace S with aSb or ab or ε (empty string). It is quite evident all strings generated will be aⁿ bⁿ for some n >= 1.

NOTE: Capital letters here are non-terminal strings and small letters are terminal strings defined as the alphabet of the language.

Let's look at another interesting grammar.

S --> SS | (S) | ε

What do you think does this grammar produce ?

Let's generate some strings and try.

So we have got (). Interesting. What else can we generate ?

So we have got (())().

An interesting property of this grammar is that it produces strings which have matched parentheses. Anyone who has written any code can understand how important it is to have parenthesis matched. This bizarre relation of matched parenthesis and our programming languages is due to the fact that syntax of most programming languages are close to context free. This answer about context-free languages shreds more light on this topic.

Here is the ANSI-C-grammar. Let's look at some part of it. Here is the part where function definition is defined 😎

Looks scary at first, but given some time its pretty trivial for any one who has written C code to abstract this out and understand this. Let me give it a shot. Let's look at the 1st and the mot complex part declaration_specifiers declarator declaration_list compound_statement.

declaration_specifiers - Maps to stuff like

extern,typedefand also to type-specifier's likeintfloatetc.declarator - Maps to the function name. Can be a complex function pointer also.

declaration_list - Maps to the arguments.

compound_statement - Maps to the function body.

Pretty easy to see what component maps to what part of the function definition. The language syntax can get complex real fast with stuff like :

But one might be surprised to know that the grammar we just saw can handle this with ease.

This is the real power of push-down-automata and context-free-grammars.

Just as we were thinking CFG's are awesome, we realize that they are also not powerful enough to generate string of the format aⁿ bⁿ cⁿ.

It's kind of impossible to believe it at first. A parser that can parse (almost) every C program in the world can't recognize strings of the form aⁿ bⁿ cⁿ.

Let's try to get an intuition on why this is not possible using PDA's. The inherent problem when we are trying to solve this with a single stack is that we are not able to count twice. We are limited by the model of our memory i.e. stack.

Let's try to solve this with 2 stacks instead of 1. With some playing around, we can come up with this scheme :

When we encounter an a we push it to the first stack. When we encounter a b, we pop a from the 1st stack and simultaneously push b to the 2nd stack. Once we start seeing c's we pop b's. If both the stacks are empty then we have identified our string aⁿ bⁿ cⁿ. I have certainly omitted some details but the crux of the idea remains the same.

We must not fall into this trap of adding more stacks or making tweaks to solve the problem at hand. What we are looking for is a model of computation that can solve a whole class of problems. It can be easily verified that the 2-stack PDA cannot accept strings of the form aⁿ bⁿ cⁿ dⁿ. For that we need 3 stacks. When we generalize this idea, we see that we require many stacks and the collection of stacks are behaving like a Random-Access-Memory. This brings us to perhaps the most important discovery in the field of computer science, the Turning Machine.

Turing Machines

There are many definitions/versions of Turing Machine and all of them are proven to have the same computational capability. We are going to look at one such version. This is a tweaked version of Informal Definition in Wikipedia.

Turing Machine consists of :

An infinite tape that consists of alphabets. The staring of the tape has a special symbol say

$and apart from the input string which starts just after the$, the all the cells of the tape have a blank symbol0on it.A head that can read/write and symbol in the alphabet from/onto the tape. The head can also move along the tape, but not left to the $ symbol.

A state register, which contains the current state of the Turing machine. One of the state is a starting state and one or more of them can be a final state.

A table of transitions which are like the instructions for the machine on what to do. All 3 are performed in this order.

Write a symbol on the current head. (Can be the blank

0also)Move the head, to the right or left.

Write a state to a state register. (Can be same as the current state)

Here is how it looks :

It contains the input aaaabbbbcccc. Z marks the end of the input string. Ok, let's now try to perform some operations to recognize strings of the form aⁿ bⁿ cⁿ with the example of a⁴ b⁴ c⁴

NOTE: The solution I describe below is very crude and may not be theoretically correct (in the sense that it covers all the corner cases) but it should give the reader a good enough intuition on this machine works.

Algorithm :

If we get an a, make is blank (

0) and move right until we get a b.If we get an b, make is blank (

0) and move right until we get a c.Go back until left-most a (Exercise for the reader on how to do this) and repeat.

If at the end (how do we define end ?), if all things are blank then the string is accepted.

Wow! We have solved a problem that we have been trying since the origin of PDA's guess what, this same machine can be used for aⁿ bⁿ cⁿ dⁿ also.

Since we have been falling for the same trick again and again, one would naturally ask, can this compute everything or is this blog going to go on forever ?

Turns out that this too cannot compute everything. There are some problems that even Turing Machines cannot solve. But we will get to that later.

To really appreciate the genius of Alan Turing, we have to understand that there were no computers in 1936. Even the transistor was invented in 1947. Turing proposed a model of computation that has stood the test of times. We still have not got a better model of computation than what was proposed over a century ago. Turing generalized the notion of computing and literally simplified it down to such a simple machine. All modern architectures strive to be Turing Complete. All programming languages try to be Turing Complete.

In computability theory, a system of data-manipulation rules (such as a computer's instruction set, a programming language, or a cellular automaton) is said to be Turing complete or computationally universal if it can be used to simulate any Turing machine. The concept is named after English mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing. A classic example is lambda calculus.

Another interesting read is how many instructions are required in an Instruction Set Architecture to be be Turing Complete. It turns out that the answer is ONE. One Instruction Set Computer.

So if all modern computing is based on a Turing Machine, then what can't it solve ?

The dreaded Halting Problem :

In computability theory, the halting problem is the problem of determining, from a description of an arbitrary computer program and an input, whether the program will finish running (i.e., halt) or continue to run forever.

Proof by Paradox 😎 :

As simple as that definition is the problem itself. There is no algorithm to determine if a program will halt or continue to run forever given all possible programs and inputs. Most of this comes from the fact that in a Turing Machine we are not constrained by Memory or Time. We have all the memory we want (in a random access fashion) and all the time we want to compute.

For eg. we send a HTTP GET request to a server and we are expecting some data back. How do we know that the server has responded and our data is on its way or not ? This is my imagination of what a halting problem would look like in real life. Well, what do we then ? We put a timeout and after that we assume something is gone wrong. This is good enough for all practical purposes but this adds an additional constraint to our machine which was not there in the original Turing Machine and hence this machine is not as computationally powerful as the Turing machine.

One takeaway question which is still unanswered is, Is the halting problem solvable in some other model of computation which is as powerful as a Turing Machine ?

Other Models

There are some other models that are currently under research :

The problem is that we are striving for speed in most of these cases which the Turing Model doesn't care at all.

There are many kinds of computation that differ from those modeled by a Turing machine. Consider analog computers, neural nets, protein regulation, quantum computing to name a few. Tempers only flair when one is argued to be faster than another.

This article sheds light on some of the myths regarding Non-Turing Computing.

Also there is this field of Hyper Computation which deals with problems that are intractable in the Turing Model.

Appendix

Contains some of the interesting topics that I have explored during this blog.

Primality Test. I really liked the Heuristic tests section where this is discussed :

These are tests that seem to work well in practice, but are unproven and therefore are not, technically speaking, algorithms at all. The Fermat test and the Fibonacci test are simple examples, and they are very effective when combined. John Selfridge has conjectured that if p is an odd number, and p ≡ ±2 (mod 5), then p will be prime if both of the following hold: 2(p−1) ≡ 1 (mod p) fp+1 ≡ 0 (mod p) where fk is the k-th Fibonacci number.

Last updated