Stack-Queue Sort

I found this very interesting question, SQSORT, while solving the JAN21 Long Challenge in Codechef. Here's the question in brief:

There are B blocks distributed in N containers, the weight of the ith block is Wi. For each container you can decide if it will behave like a stack or a queue. In one operation you can pop a block from one container and push it to another container. The cost to pop a block of weight w from container i is Ci Wi, and the cost to push it to container j is Di Wi. Find the minimum cost to sort all the blocks in one of the containers.

This was given as part of the contest as a tie-breaker where the best solution got 100 points and all the rest of the solutions got points relative to the best solution. This is generally known as a "Challenge" question in the Codechef long challenges.

Okay! Let's think of some strategies to solve this problem.

Brute Force ?? 😈

A good way to solve any problem when you don't have an obvious solution or logic to it is to solve it using brute force first and then to improve on it!

For each container, we have to choose whether its a stack or a queue. For N containers that's 2N choices there itself.

Let's say we have to move K blocks from one container to the other so that the final result is sorted.

To do this we need to choose 2 containers and perform that operation K times.

Number of ways to do this for a given K is ( NC2 ) K

We can only do this operation B2/2 times. So K ≤ B2/2

Therefore our total time complexity is 2N * Σ ( NC2 ) K where K ∈ {1, 2, 3 ... , B2/2}

We can easily see that this is going to be exponential in nature. But how do we know we can't do better ?

Proving NP-Hardness

How do we prove a problem is NP-Hard ? What is NP-Hard ? Let's explore a bit but not too much.

What's P, Co-NP, NP-Hard, NP-Complete etc. ?

Complexity: P, NP, NP-completeness, Reductions, a lecture from MIT explains this the best!

P = Problems solvable in polynomial time

NP-Hard = A problem X is NP-Hard if all problems in NP can be reduced to X.

Let's look at a solution to SQSORT which is in polynomial time.

Let's guess correctly for each container whether its a stack or queue.

Let's correctly make these pop-push moves from source containers to the destination containers such that at the end of the all these operations we have a sorted container.

Notice the emphasis on "correctly", Non-Determinism is what helps us to do that. Ofcourse, we don't have such computing machines which work on non-determinism, so even though we have an algorithm to solve this problem, we don't a a machine which can solve it (yet).

To prove that its NP-Hard, we would need to reduce it to another "hard" problem. Reading up some literature on the problem and similar ones with different contraints (relaxed) one can stand on the shoulders of giants and say that this is indeed NP-Hard for N > 3. Some interesting papers that I referred while trying to understand existing literature on this problem are:

Show me some strategy! 😑

For those who are here to see interesting strategies for this problem, I shall keep you waiting no more.

Firstly I personally found it difficult to use stacks to solve this problem only to realise that the problem is more or less the same whether we use stacks or queues to find "a solution".

So in the strategies that I am going to discuss below, it will mostly involve just using queues. So here we go.

Some observations:

The problem is trivial when N > B

Since we cannot push and pop into the same container, we need atleast 3 containers to solve this problem for the worst case.

We need 1 container to hold the solution which is the final sorted array. This leaves us with 2 containers from where we push and pop the blocks.

A solution ✅

Let's find a solution which just does the job without worrying about optimality.

Say we have B blocks distributed over N containers initially.

Choose 2 containers C0 and C1 as the primary and the secondary containers

Empty every other container into C0 (primary container)

Now choose any empty container (N - 2 containers are now empty) as the container where we will have the final sorted blocks. Let this be C3 for now.

Now empty all blocks in C0 one by one.

If the block does not break the sorted order in C3, push it to C3.

Else, push it to C2.

Now container C1 is empty.

Swap container C1 and C2. This is just a logical swap, no operation is done here.

Goto Step-5.

Exit when C0 has no more blocks left. At this point C3 will have all blocks sorted.

It's not hard to see that this solution is a valid one. It pushes the next consecutive block into A everytime.

It's also not hard to see that this is a very slow solution. But let's see in the worst case how many pops and pushes we have to do in this algorithm.

In the worst case if all the elements are in reverse of sorted order, we have to do this operation at-most B times each time operating on B - i blocks in the ith iteration.

Why are we doing bad ? 💩

In the original problem the number of blocks are fixed. B = 1024. In addition the number of containers are also from the set N ∈ {16, 32, 64, 128 }

The problems with our current approach: 1. We are able to sort only ONE block at at time. Can we sort multiple elements at a time ? Some sort of Divide and Conquer ? 2. A lot of unnecessary blocks are being pushed and popped despite the fact that they are not relevant at the current moment in time. For eg. the block 750 is not going to be pushed into the solutions container nowhere in the first 749 iteration, so can we keep it stored somewhere and bring it back only when its time ?

Let's better our current approach ⏩

Let's try to solve the 1st problem in our solution. We do this by borrowing ideas from Merge Sort and Quick Sort. We divide and conquer using two different strategies: 1. Sort sub-problems and merge. (Merge Sort) 2. Partition and solve sort the sub-problems. (Quick Sort)

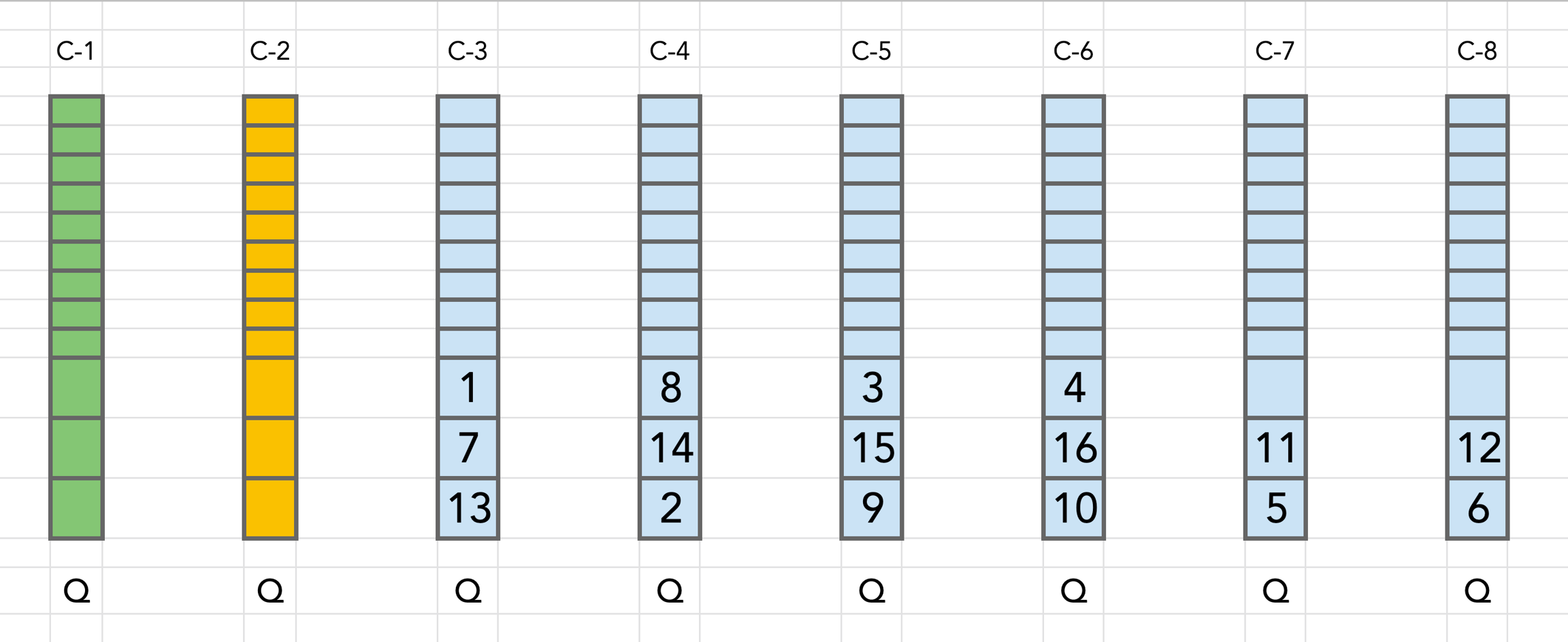

Note: 1. Containers C1 (Green) and C2 (Yellow color) are our "working" containers which will be used to transfer blocks from one another. 1. We chose C1 as the primary container (denoted as 🟢 from here on) 2. We choose C2 as the secondary container (denoted as 🟡 from here on) 2. Containers C3 - C8 (Blue color) are our "sorting" containers.

The Merge Sort like approach

The key idea is to use multiple containers to keep the sorted portions of the whole set of blocks and then merge them.

Let's use K = N - 2 blocks as the different containers for partial sorting.

If there is a block with number i, then it goes to (i % K)th container.

Then we can merge the K containers into one of the containers.

This is how the intermediate state looks like for B = 16 and N = 8

The Quick Sort like approach

Notice that in the Merge Sort appraoch, the containers C3 - C8 have all the elements sorted in them. The problem is that to get to this intermediate state it takes a lot of iterations. Block-7 can be inserted into C3 only after Block-1 is inserted.

In quicksort partition, we don't care about the order of the elements itself while putting them into the "left" and the "right" partitions. Let's try to do that. This we can finish in a single iteration over all the blocks.

This is how the intermediate state might looks like for B = 16 and N = 8

Now we go through all the containers C3 - C8 and sort them and put them into C0.

The Merge Sort based approach performs better than the Quick Sort based approach. I don't have a very solid reasoning for this, but here's my take on it.

The number of iterations in Quick Sort based approach to move all the elements to their respective containers is just 1.

The number of iterations in Merge Sort based approach to move all the elements to their respective containers is at most B / (B / K) = K

The key idea is that atleast K elements get placed in their correct positions in an iteration.

The trade off is between sorting all the smaller unsorted containers vs doing K iterations and then just doing a single merge.

Que: Could we have split the containers further to allow multiple levels of further quicksorts on the smaller containers ?

Ans: Yes. But I did not try this approach as it would have been slightly tricky to implement this.

Both these approaches were trying to solve the divide and conquer problem that we described in the section before.

Now let's try to solve the other problem that we had in our approach.

The problem of idle blocks 💤

Now that the Merge Sort based approach is doing better, let's try to solve the problem of higher numbered blocks being idle in the queues rather than reaching their destination quickly.

Let's create some buffer containers where we temporarily store the higher numbered blocks instead of them shuffling in between the queues while we distribute.

If we have P = 2, K = 4, N = 8, B = 16 buffer containers, this is how things would look like in one of the intermediate states.

Here C7 and C8 (Red colored) are buffer containers. We divide our data into (P + 1) roughly equal sets { 1, 2, ..., 6} , { 7, 8, ..., 11 }, { 12, ... , 16 }.

While the set {1, 2, ..., 6} is being sorted, the other 2 sets with higher valued blocks are lying idle in the buffer containers. This saves us a huge amount of cost of transferring them between C1 and C2 while sorting the lower valued blocks.

Choosing the number of buffer containers ? 📚

Now that we have clearly seen the effects of adding in buffer containers, we need a strategy to choose the number of buffer containers.

I tried values from 0 to min(32, N/2) and found that the best value for each N and each configuration was different but was lesser than 8 for the given instances of the problem. So the process of finding the optimal value of P (number of buffer containers) had to be ingrained in the program itself.

Choosing the right containers 📦

Till now we haven't even taken into account the cost to push/pop a block from containers and haven't optimised on that front. A simple strategy here would be to use the heuristic of Ci + Di as the the "goodness" of a container.

We use the best containers as the "working" containers (the one indicated in Green and Yellow) which have the maximum elements pushed/popped into them so as to minimise the costs.

We use the next best containers for the buffer containers as they will see more number of operations on them than the rest of the containers which will contain the partially sorted blocks.

NOTE: Reassigning of containers is not that trivial in implementation as our modulus operation to attach a block with a container now needs an additional step of remapping the indices for each container with the next free container.

Another optimisation is to add blocks having bigger Wi to containers having smaller Ci + Di as this would minimise the product.

Queues vs Stacks

Till now we have been using our containers as queues, but the solution that we have discussed till now doesn't require the container to be a queue. The exact same approach can work with all the containers as stacks as well.

Que: Is there any optimisations that we can do here to choose which containers are queues or stacks based on the order of the elements appearing on the containers ?

Ans: Probably Yes. But this is not something I had explored during the contest. Currently I don't have a good enough strategy to allocate stacks/queues to containers. Will update this post if I find one.

Some more optimisations 😅

We have been emptying containers in the beginning and putting them all in either of the 2 containers (green/yellow) to start the sorting process. This step can be skipped by maintaining which element was on the back of each queue initially and processing elements only till that time. NOTE: This requires that our blue containers are all queues, as if they were stacks, they would not be able to do this optimisation.

Some blocks might already be present in buffer containers which they belong to. As we can't pop/push on the same container, we can use the primary container as a stack instead of a queue so that we can use it as a buffer/temporary storage and then push it back to the correct buffer container. This would be optimal as the primary container has the least cost of pushing and popping a block.

In the very first step for pushing all the "working" blocks to primary/secondary containers, we can always choose the block which is the smallest in front of all the queues and push that first. Smaller blocks at the front of the queue will help in faster placement of blocks.

Here's my solution with more or less all the optimisations discussed above: https://www.codechef.com/viewsolution/41576033

Conclusion

Overall it was a very interesting problem to solve and optimise. I learnt a lot during the contest while solving the problem and after the contest by looking at other people's solution which were better than mine.

The good thing about this problem is that it doesn't require knowledge of fancy data structure or algorithms to solve it. Stacks, Queues and Sorting. That's all!

The [SQSORT-Editorial] for the problem is also pretty nice and has some thoughts and ideas that I hadn't explored. The approach discussed in this post is fully deterministic whereas there are interesting randomised algorithms which yield better results in some cases.

[SQSORT-Editorial]: https://discuss.codechef.com/t/sqsort-editorial/83119

Last updated